Readers of the World: Romania

It's that time again where we head off to another destination on our worldwide whistle-stop tour of literary wonders and delights, and catch up with our Readers of the World. Last time we took in the sights - or more appropriately, the words - of Israel; where will we be picking up a souvenir postcard this time around? Well, we can tell you right now: we're going to Romania (thanks to former Communications Intern Mike Butler). Without further ado, let's take off and read on...

If you think capitalism’s bad – mass privatisation, rising inequality, BT adverts – then, before you decide to collectivise your land, buy a tractor and denounce your next-door neighbour to the Securitate, you might first want to read Herta Muller’s The Land of Green Plums, set in 1970s Romania during Nicolae Ceausescu’s Communist dictatorship. Muller was an eyebrow-raising (i.e. not Philip Roth) winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2009, but LGP’s unflinching depiction of the everyday horrors and banalities of life under the regime is enough to silence any Anglophone complaints about the supposed eccentricities of the awarding committee.

If you think capitalism’s bad – mass privatisation, rising inequality, BT adverts – then, before you decide to collectivise your land, buy a tractor and denounce your next-door neighbour to the Securitate, you might first want to read Herta Muller’s The Land of Green Plums, set in 1970s Romania during Nicolae Ceausescu’s Communist dictatorship. Muller was an eyebrow-raising (i.e. not Philip Roth) winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2009, but LGP’s unflinching depiction of the everyday horrors and banalities of life under the regime is enough to silence any Anglophone complaints about the supposed eccentricities of the awarding committee.

The novel, largely autobiographical, is told from the perspective of a female German-Romanian student who, along with her three male friends, comes to the attention of the secret police and is subjected to harassment, spying and interrogation. The sparse and sometimes enigmatic narration convincingly captures the psychological effects of living within a strictly circumscribed reality, in which individual thought and expression are oppressed.

It’s not a barrel of laughs - the narrative is driven largely by suicide, madness and despair – but the narrator, at once jaded and unworldly, gives the prose a captivating, deadpan quality: her ‘heart-beast’ leaps out of her chest and onto the floor; she observes her ex-SS father hacking at the ‘damn stupid plants’ in the garden; the factory workers in the city produce ‘tin sheep’ and ‘wooden melons’ with their provincial hands. LGPs could be read as a realist counterpart to George Orwell’s 1984, inhabiting a similar world in which your best friend can be your worst enemy, and in which the present tyranny seems to stretch on forever.

Self-expression and independent thought are virtually impossible in The Land of Green Plums, but the characters in Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros face identity issues of a more extreme variety – namely, that everyone starts turning into rhinoceroses. First performed in Paris in 1960, seven years after the premiere of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, the two main characters in this play don’t have to wait around very long for a mystical appearance. A rhino comes crashing down the street, trampling a cat but leaving the Sunday-afternoon ennui largely intact: one character, asked what he thinks of the incident, remarks, ‘Well … nothing … it made a lot of dust …’

Soon, however, everyone’s at it, and the chaos and destruction intensify; the moral recrimination begins and the remaining humans form a mini-resistance to the violent occupation. The meaning of the play would have been fairly unambiguous to a Parisian audience in 1960, sixteen years after the end of the Nazi occupation of the city; the characters often speak in terms of collaboration and betrayal (‘I never would have thought it of him – never!’), whilst allowing themselves to give in to denial and resignation (‘we must move with the times!’).

Typically of absurdist theatre, the nightmarish and the comic are combined: in one horrific scene, which looks back to Kafka’s Metamorphosis and forward to David Cronenberg’s The Fly, the character Berenger witnesses his best friend Jean turning into a rhinoceros; rapidly turning green and becoming hoarse, he renounces humanist values and cries out for ‘The swamps! The swamps!’ Later on, Berenger recognises the straw boater pierced on the horn of a recently transformed ex-human: ‘The Logician … a rhinoceros!!!’ ‘He’s still retained a vestige of his old individuality,’ observes his colleague of the disembodied head bobbing along the orchestra pit.

The characters in the play summon several discourses – logical, legal, medical, relativist – in order to explain and come to terms with their bizarre predicament, but all are shown to be inadequate. Where Rhinoceros ends with a flourish of humanistic defiance, however, no such consolation is offered in the work of the philosopher E. M. Cioran, who in his A Short History of Decay (1949) blames the human inclination toward belief and fanaticism for the sufferings of the world. Such nihilistic sentiments were probably not uncommon after the Second World War, especially if you’d spent most of the 1930s in Germany describing yourself as a ‘Hitlerist’ and expressing your support for the fascist Iron Guard back home. ‘Once man loses his faculty of indifference he becomes a potential murderer; once he transforms his ideas into a god the consequences are incalculable,’ he writes after the war.

For those of us who embrace nihilism as a convenient excuse to sit around shrugging our shoulders and eating crisps, Cioran comfortingly assures us that ‘ennui is the echo in us of time tearing itself apart,’ which, if true, certainly adds a sheen of philosophical respectability to watching Jeremy Kyle on a grey Tuesday afternoon. If you are feeling ennui-stricken and missing the rumble of rhinoceros hooves or of time tearing itself apart, then you could do worse than read Andrei Codrescu’s The Posthuman Dada Guide, written in the playful and subversive spirit of the movement that it celebrates.

The Romanian Tristan Tzara was one of the founders of Dadaism, which came to prominence during World War I - a time when ‘like a spectator watching splendid mannequins being outfitted for the evening by a tailor (Mr. History), Romania gathered the leftover scraps to make its own, rather improvised, suit from the elegant remnants,’ according to Codrescu, referring to its post-war acquisition of Transylvania and Bessarabia and resultant cultural variety. Like Cioran, the Dada artists and writers saw the modern world as inherently meaningless, but they celebrated rather than mourned this fact (which is possibly the crucial – if in this case achronological – difference between postmodernism and modernism). Romanian writers in the twentieth century seem constantly to be staring absurdity in the face, as Europe cracks up and realigns itself, then cracks up again; Romania joined the EU, with its promise of stability, in 2007, and may find itself caught in this cycle once more.

Share

Related Articles

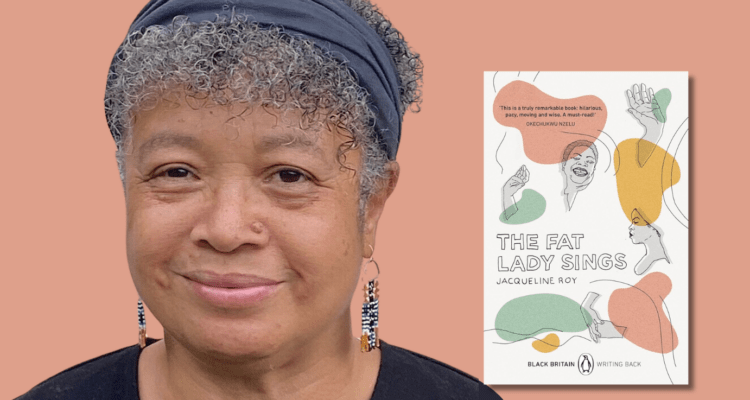

In Conversation with ground-breaking dual-heritage author Jacqueline Roy at The Reader, Liverpool.

The author Jacqueline Roy will be in Liverpool discussing her ‘forgotten’ novel The Fat Lady Sings, republished as part of…

Artisan upcycler on BBC’s Money for Nothing is leading free workshops for The Reader’s Upcycling group

Friendly weekly Upcycling group at Calderstones Park is looking for new members, launching a Saturday group and appealing for furniture…

Liverpool Shared Reading charity’s Christmas appeal donations nearly hits £10,000 target

National Shared Reading charity The Reader pays tribute to supporters' generosity across the North West for helping to fund the…

1 thoughts on “Readers of the World: Romania”

[…] time we went off to Romania; this time around we’re heading to the second-most populated country in the world – so there […]